When Andhra Pradesh began helping millions of farmers switch to Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF), the world paid attention. The scale was huge — six million farmers across almost every district. But the method was even more surprising.

Instead of using chemical fertilizers or pesticides, ZBNF builds a full farming system using simple, natural tools. Farmers rely on fermented mixtures, thick mulching, mixed crops, and strong soil biology.

But this leads to a big question: How does something so large actually work in daily farm life?

The answer shows one of the most inspiring and practical agroecology transformations happening anywhere in the world..

The Engine of ZBNF: A Fermented Microbial Solution Made on Every Farm

At the core of ZBNF is Jeevamrutham, a fermented mix made from:

- Cow dung

- Cow urine

- Jaggery

- Pulse flour

- Local topsoil

- Water

It is the “starter culture” that activates soil microbes and supports long-term fertility.

How Much Does One Batch Produce?

A standard preparation creates 200 liters of Jeevamrutham.

The Exact Mixing Ratio (Field Standard)

A 200-liter batch — enough for 1–2 acres — is produced using:

- 10 kg cow dung

- 5–10 liters cow urine

- 2 kg jaggery (molasses)

- 2 kg pulse flour (e.g., chickpea flour)

- 1–2 handfuls local topsoil (microbial inoculant)

- Water to complete 200 liters

The ratio can be scaled up or down for any farm size, but the proportions remain constant.

This level of simplicity is intentional — it ensures that a farmer in a remote village has the same access as a farmer near a distribution network.

How Farmers Actually Mix It

Most farmers prepare the solution in a plastic drum or concrete tank:

- Add 150–170 liters of water.

- Mix in 10 kg fresh cow dung.

- Add cow urine and stir thoroughly.

- Dissolve jaggery and pulse flour.

- Add topsoil to introduce native microbes.

- Stir vigorously.

- Allow to ferment 5–7 days, stirring twice daily.

The mixture develops a sweet, fermented aroma — a sign of strong microbial growth.

How Much Land Does It Cover?

One 200-liter batch can treat 1–2 acres depending on soil quality and crop type.

- New-to-ZBNF soils → farmers use a slightly higher quantity

- Mature ZBNF soils → require less frequent use

This is what makes the system extremely low-cost and scalable.

decentralized, farmer-made — not factory-made

One of the most common misconceptions is that Jeevamrutham is produced in a central facility and distributed like fertilizer.

In reality, every farmer produces it on their own farm — and this is intentional.

Why decentralized production?

- Ingredients are local and cheap

- Fresh microbial mixtures work best

- Farmers gain skill instead of depending on suppliers

- Transport costs drop to zero

Each farmer mixes the ingredients in a barrel, stirs the solution twice a day for 5–7 days, and applies it through irrigation or simple watering cans.

There is no central manufacturing site. There are thousands of micro-production units, each located on individual farms.

This is one of the secrets behind how ZBNF reaches such massive scale.

What Crops Are Grown Under ZBNF?

ZBNF is not crop-specific. It has been adopted widely for:

Staple Crops

- Rice

- Wheat

- Millets (finger millet, foxtail, kodo)

- Pulses

Commercial Crops

- Cotton

- Groundnut

- Sugarcane

- Vegetables

Horticulture

- Mango

- Banana

- Papaya

- Citrus

- Coconut

Spices & Niche Crops

- Turmeric

- Ginger

- Red chili

Because the system builds soil biology rather than feeding the plant directly, almost any crop can be grown under ZBNF with proper crop planning.

How Farmers Join the ZBNF Movement: The Ground-Level Process

ZBNF spreads through a large, community-driven extension model supported by the Government of Andhra Pradesh and farmer groups.

- Enrollment Through Community Organizations

Farmers typically join through:

- Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs)

- Women self-help groups

- Village-level committees

These networks make outreach fast and trust-based.

- Village Training Camps (Polam Badi)

Trainers hold hands-on field classes where farmers learn:

- How to prepare Jeevamrutham

- Mulching techniques

- Intercropping models

- Botanical pest control

- Soil health testing

- On-Farm Demonstration Plots

Farmers try ZBNF on ¼ or ½ acre first.

When results show:

- lower input cost

- equal or better yields

- improved soil texture

…they expand to full acreage.

- Peer-to-Peer Mentorship

Experienced farmers mentor newcomers — the strongest driver of adoption.

- Continuous Field Support

Trained community resource persons visit fields weekly to guide farmers during the first year.

This decentralized extension structure is what connects thousands of farmers without relying on one central facility.

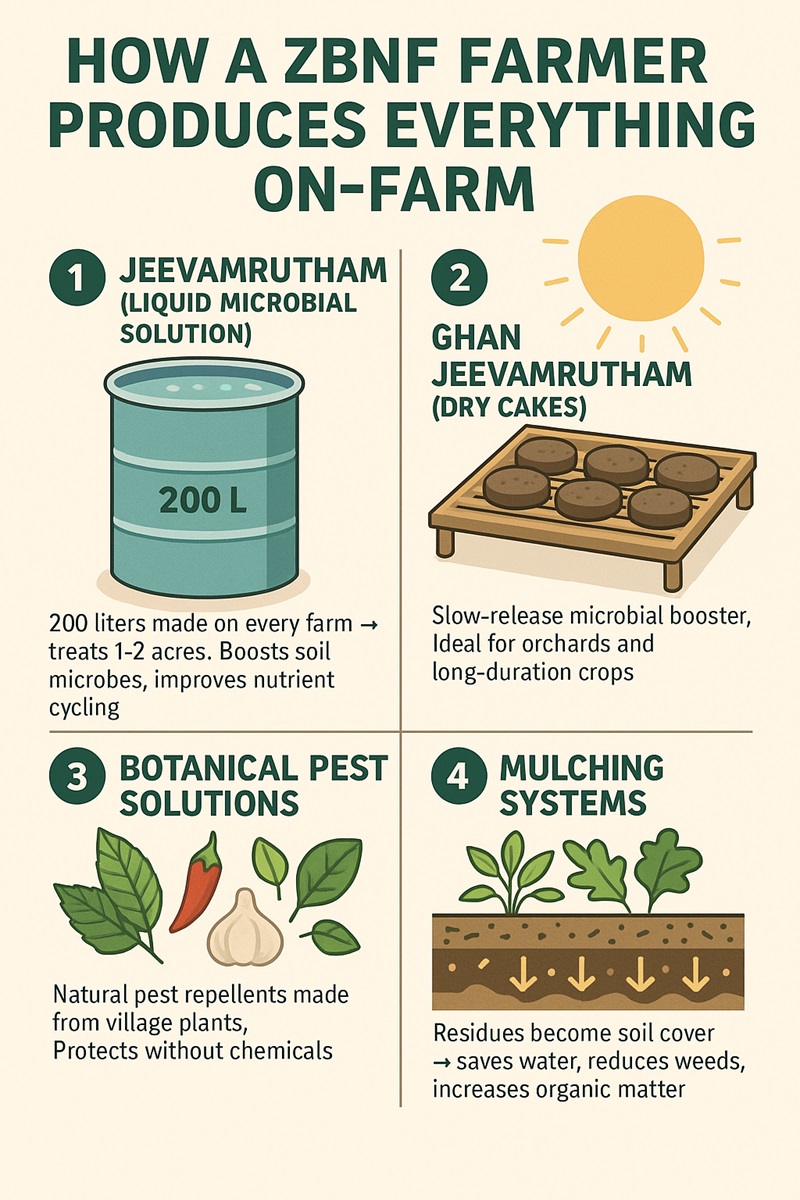

What Farmers Produce on Their Own Farms — The Heart of ZBNF

One of the strongest parts of Zero-Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF) is that every farmer becomes a maker, not a buyer. Instead of depending on fertilizer shops or long supply chains, farmers create almost everything they need right on their own land. The materials come from the farm, the village, or nearby fields.

The main input is Jeevamrutham, a fermented mix that boosts good microbes in the soil. But farmers also prepare three other key items: Ghan Jeevamrutham, plant-based pest sprays, and different types of mulch. Each one supports soil life in a simple, natural way.

Together, these homemade inputs help the soil, plants, and microbes work as a single, self-sustaining system.

1. Ghan Jeevamrutham: The Dry Microbial Booster

Ghan Jeevamrutham is the solid, shelf-stable version of the liquid fermentation already used in ZBNF. Farmers make it by mixing the standard ingredients — cow dung, cow urine, jaggery, pulse flour, and a handful of native soil — into a thick paste rather than a liquid.

Once mixed, the paste is shaped into small, round cakes and left to dry in the sun.

Why farmers use it:

- It delivers the same microbial power as the liquid version but in a slow-release form.

- It is ideal for orchards, plantations, and perennial crops where longer nutrient cycles matter.

- It stores easily for months, allowing farmers to plan ahead and reduce labor during peak seasons.

- It helps re-establish microbial life in degraded soils — a common issue in monoculture belts.

Farmers often place the dry cakes near the base of fruit trees or incorporate them lightly into the soil during field preparation. Over time, the cakes absorb moisture, break down slowly, and release beneficial microbes that support continuous root development.

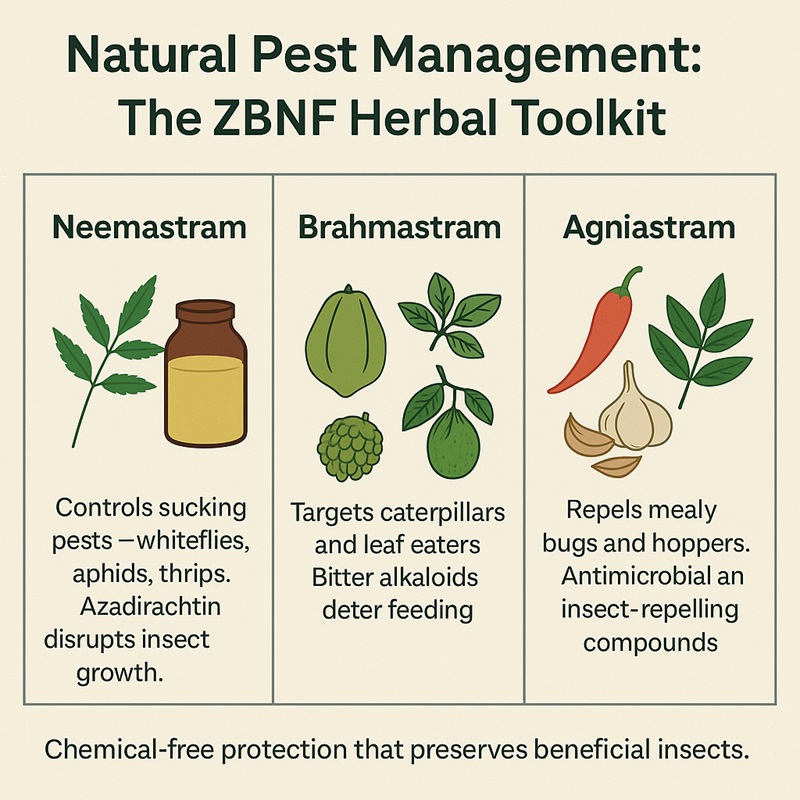

2. Botanical Pest Solutions: The Village Pharmacy That Protects Crops

Instead of purchasing chemical pesticides, farmers create their own plant-based pest management formulations, relying on bitter leaves, herbs, aromatic compounds, and natural alkaloids found in the hedgerows and common village trees.

These botanical extracts work not by poisoning pests but by disturbing their feeding patterns, repelling them, reducing egg-laying, and strengthening plant immunity.

A Few Common ZBNF Formulations

• Neemastram

A neem-based spray used to protect crops from pests like aphids, thrips, and whiteflies.

Farmers ferment neem leaves and seeds with cow urine. This creates a mix rich in azadirachtin, a natural insect blocker.

• Brahmastram

A strong herbal spray made from the leaves of custard apple, papaya, datura, guava, and neem.

It helps control caterpillars, pod borers, and leaf-eating insects by reducing their feeding and lowering how many larvae survive.

• Agniastram

A spicy mix made with green chilies, garlic, neem, and cow urine.

Farmers spray it on crops to manage mealybugs, hoppers, and small fungal issues. It serves as a natural replacement for chemical pesticides.

Why These Formulas Matter

These homemade sprays protect crops without harming helpful insects like:

- Ladybird beetles

- Parasitoid wasps

- Bees

- Soil fungi

By avoiding chemical pesticides, farms slowly return to natural balance.

Pest attacks become less common, natural predators come back, and farmers can grow food without chemical residues.

3. Mulching Systems: Turning Farm Waste Into Ecological Wealth

Where conventional farming burns residues or leaves soil bare, ZBNF treats every stalk, leaf, and husk as a valuable ecological asset. Mulching is not optional — it is a core pillar that determines how moisture moves, how microbes grow, and how resilient the soil becomes over time.

Soil Mulch

Farmers cover the soil with crop residues — rice straw, maize stalks, dried leaves, husks, shredded stems. This blanket protects the topsoil, reduces evaporation, and slows weed emergence.

Live Mulch

Green cover crops like cowpea, sunhemp, horse gram, or pigeon pea are grown between rows. They shield the soil, feed root-zone microbes, add organic nitrogen, and naturally outcompete weeds.

Vertical Mulch

Organic matter is placed into narrow trenches dug between crop rows. As it decomposes downwards, it improves deep soil moisture, supports root expansion, and increases organic carbon levels.

What farmers experience:

- A “spongier,” softer soil texture

- Stronger root development

- Drastic reductions in irrigation needs

- Lower weed pressure without herbicides

- Higher microbial activity under the covered soil

Mulching transforms the farm floor into a living sponge — much like the forest floor — allowing crops to weather drought, heat waves, and irregular rainfall far better than conventional fields.

Together, These Inputs Create a Truly Self-Reliant Farm

By producing:

- Jeevamrutham (liquid microbes),

- Ghan Jeevamrutham (slow-release microbial cakes),

- Botanical pest solutions (plant-based crop protectants), and

- Mulch (ecological soil cover),

each farmer becomes the manager of a complete biological system — not a consumer in an input market.

This is why ZBNF scales so effectively across thousands of villages: it’s not built on factories or supply chains, but on local knowledge, decentralized production, and ecological cycles that regenerate themselves.

No dependency on external suppliers

Unlike chemical agriculture, there is:

- No fertilizer factory

- No pesticide company

- No centralized distribution network

ZBNF spreads like an “ecological franchise,” where knowledge replaces chemical inputs, and bio-cultures replace purchased fertilizers.

Community groups coordinate

- Training

- Seed exchange

- Micro-credit support

- Collective marketing of natural produce

Thousands of farmers remain connected not through a product supply chain, but through a knowledge and training ecosystem.

Why Soil-Based Systems Scale Better Than Input-Based Systems

Chemical agriculture scales through factories.

Agroecology scales through skills and soil biology.

For a project of this scale to succeed:

- Farmers must be empowered, not dependent

- Inputs must be locally available

- Practices must be simple and repeatable

- Costs must be extremely low

ZBNF meets all four criteria.

The Broader Impact: What Andhra Pradesh Demonstrates to the World

The ZBNF experiment reveals that large-scale agroecology can work when:

- Knowledge is decentralized

- Production is hyper-local

- Farmers are owners of the process, not buyers

- Government support accelerates adoption

- Peer learning replaces corporate supply chains

It is a model many climate-stressed regions are now studying — from Africa to Southeast Asia — to reduce input dependency, build soil health, and stabilize farmer incomes.