For centuries, water has shaped the identity of Bengal. Bangladesh’s rivers and canals are more than waterways—they are lifelines for agriculture, transport, and resilience against floods. Bengal’s history even shows that irrigation canals were dug nearly three thousand years ago.

Dhaka itself once boasted around 65 canals, connecting neighborhoods and easing monsoon waterlogging. Today, surveys vary: some list 43–50 still functioning, while others suggest only 26 remain. The decline has been stark. A study by the River and Delta Research Centre (RDRC) found the capital lost nearly 120 km of canal length—about 307 hectares—since the 1940s to encroachment and neglect.

Dhaka: Once a “City of Canals”

Long before cars and concrete, water shaped Dhaka’s story. In the Mughal era, the city was called the “Venice of the East.” Canals like Dholaikhal, Segunbagicha, and Narinda were busy trade routes. They connected rivers to markets and carried boats full of jute, spices, and textiles.

When Subedar Islam Khan made Dhaka the capital of Bengal in the early 1600s, he ordered the digging of Dholaikhal. It boosted trade and also protected the city from floods. These canals were more than waterways—they were part of Dhaka’s culture, economy, and safety. Losing them is not just an environmental issue. It also means losing part of the city’s identity and history.

From Resource to Risk

Today, that proud legacy is in danger. Unplanned growth, illegal land grabs, garbage dumping, and neglect have turned flowing canals into stagnant waste pits. Where boats once moved and children played, people now face bad smells, mosquito swarms, and waterborne diseases.

The price is high. Dhaka’s two city corporations spent more than Tk 30 billion in the past 12 years fighting waterlogging. Yet residents still suffer. Studies show that in some years, poor families lost up to 8% of their income due to flood damage, health care costs, and lost workdays.

Lost & Surviving Canals of Dhaka

| Canal Name | Current Status | Condition / Issues |

| Dholaikhal | Lost | Box-culverted, filled; once a major canal in Old Dhaka |

| Segunbagicha Canal | Lost | Filled/encroached, no flow |

| Kathalbagan Canal | Lost | Disappeared, built over |

| Narinda Canal | Lost | Once vibrant, now lost to development |

| Panthapath Canal | Lost | Completely filled |

| Dhalpur Canal | Lost | No longer exists |

| Pandu River/Canal | Lost | Disappeared, once connected urban lakes |

| Miran Jalla | Lost | Identified as vanished in waterbody studies |

| Begunbari Canal | Survives poorly | Narrowed, encroached, polluted |

| Hazaribagh Canal | Survives poorly | Average width reduced to ~8.8m; waste-filled |

| Katasur Canal | Survives poorly | Reduced to ~6m width; heavy encroachment |

| Khilgaon-Basabo Canal | Survives poorly | Choked with solid waste; flow obstructed |

| Baistake Canal | Survives poorly | So filled with waste that people can walk across |

Sources: Dhaka Tribune, The Daily Star, RDRC, ResearchGate studies

Health & Social Impacts of Lost Canals

The loss of canals has not only hurt drainage but also made health risks worse. Stagnant, garbage-filled water becomes a perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes. This has led to rising cases of dengue and chikungunya. The World Health Organization warns that poor water systems in South Asian cities fuel the spread of these diseases.

For low-income families, clogged canals mean flooded homes, unsafe drinking water, and higher medical bills. A study in 2017 found that some families in Dhaka lost up to 8% of their yearly income because of flood damage and health costs.

Children face the biggest danger. Polluted water causes diarrheal disease, which is still one of the main causes of child deaths in Bangladesh.

Climate Resilience and Flood Protection

Dhaka consistently ranks among the world’s most climate-vulnerable cities. With more intense rainfall, the risk of flash floods grows every year. Canals act as natural buffers, absorbing excess stormwater and channeling it into rivers. When they are blocked or encroached upon, water has nowhere to go—leading to hours or even days of waterlogging.

Restoring canals is more than an urban beautification project; it is a low-cost, nature-based adaptation strategy. While Dhaka invests billions in pumps and drainage systems, studies show that reviving just 15 canals could solve up to 80% of waterlogging problems.

A Collaborative Effort: #CholoKhaalBachai#

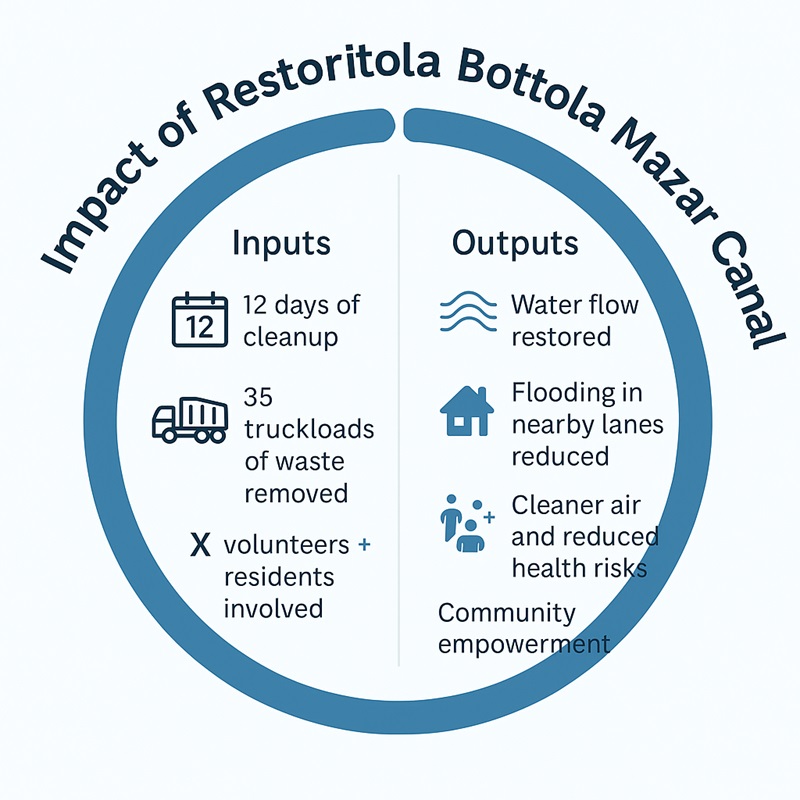

In the middle of this crisis, Berger Paints Bangladesh and Footsteps Bangladesh started the #CholoKhaalBachai# campaign. It is a volunteer-led effort to bring canals back to life. Their latest work focused on the Bottola Mazar Canal in Hazaribagh, which had become little more than an open garbage pit.

In just 12 days, more than thousand volunteers and residents removed 35 truckloads of waste. For the first time in years, water could flow again. The cleanup reduced flooding, improved air quality, and lowered health risks for hundreds of families.

“This is not charity—it is survival,” one local leader said. “We cannot afford to lose our canals.”

Linking Local Action to Global Goals

This project connects directly with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, especially SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities).

Berger Paints has also worked to reduce pollution. The company now makes lead-free, low-VOC, and APEO-free paints. It even launched Bangladesh’s first anti-pollution paint that absorbs greenhouse gases. But beyond products, the real lesson is in the model: a business, a youth nonprofit, and the community working together for urban renewal.

Policy & Governance Challenges

Yet, big challenges remain. Dhaka WASA, RAJUK, and the city corporations all share canal responsibilities, but their coordination is weak. Laws exist to stop land grabs, but enforcement is poor.

Encroachment continues. Developers, sometimes powerful ones, take land along canals. Cleanup drives are launched, but garbage and illegal structures often return within months. Without stronger oversight, these efforts risk becoming symbolic instead of lasting.

Experts say Dhaka needs one lead authority for its water bodies. They call for tougher law enforcement, community monitoring, and long-term planning to make canal recovery permanent.

Beyond One Canal: What Comes Next?

The cleanup of the Bottola Mazar Canal is a big win, but the work cannot stop here. To keep canals alive, experts say Dhaka needs:

- Community monitoring to stop people from dumping waste again.

- Policy enforcement to block land grabs.

- Public education so people see the link between trash and water safety.

- Scaling up the model to restore Dhaka’s 26–50 remaining canals.

Other cities show this can work. Singapore and Ahmedabad, India cleaned up their waterways through strong partnerships between the public and private sectors. Dhaka can adapt these lessons in its own way.

Future Vision: A Dhaka with Restored Canals

Dreaming of a Dhaka with clean canals is not fantasy—it is possible. Restored canals could bring:

- Less flooding and lower repair costs for families.

- Better health, with fewer waterborne diseases.

- Green corridors, new parks, and even eco-tourism.

- Economic growth, since homes near clean water rise in value.

Cities like Seoul transformed with the Cheonggyecheon Stream project, and Singapore’s Kallang Basin blends flood control with recreation. Dhaka, too, can see canals not as drains but as treasures—part of a safe, modern, and livable city.

Editorial Takeaway

The revival of Bottola Mazar Canal shows what is possible when businesses, nonprofits, and citizens unite. It is not just CSR—it is a vision for urban survival.

For Dhaka, the stakes are high: clean canals mean reduced flooding, better health, and a more livable city. For Bangladesh, initiatives like #CholoKhaalBachai# may mark the beginning of a new mindset—where waterways are protected as critical infrastructure rather than abandoned as waste pits.

As one volunteer put it: “We cleared garbage, but what we really restored was hope.”