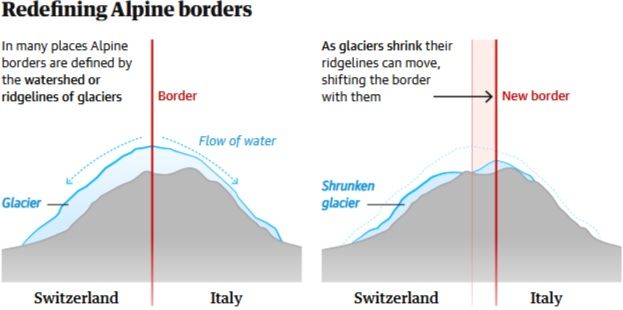

The iconic pyramid of the Matterhorn, straddling the frontier between Switzerland and Italy, has long been a symbol of Alpine permanence. For centuries, its high-altitude glaciers, including the Theodul Glacier on the Swiss side and the Plateau Rosa ice fields on the Italian flank, served as frozen, natural demarcation lines. These immense rivers of ice were so stable that they formed the basis for the border treaty signed between the two nations in 1861, later reaffirmed in 1941. The border was defined along the main watershed of the Alpine ridge, a line physically etched into the glacial ice. However, the last few decades have witnessed a profound and visible transformation, eroding this centuries-old foundation.

Rising temperatures in the Alps, which are increasing at roughly twice the global average rate, have triggered a catastrophic retreat of these frozen giants. The Theodul Glacier has thinned dramatically, pulling back from the rocky ridges it once covered. Similarly, the glacial basins on the Italian side have shrunk, exposing vast areas of bare rock and shifting moraine. This melt has fundamentally altered the natural ridgelines and watersheds. The border, once following a clear line on the ice, now in places traverses unstable rock faces or empty air where glaciers have vanished entirely. The geographic context is crucial: these glaciers historically defined the border precisely because they represented the most enduring and topographically clear features on the high mountain landscape, a logical choice in an era before satellite surveying but one predicated on a climate that no longer exists.

Switzerland and Italy: Peaceful Adaptation to Climate Change

Faced with a border literally melting away, Switzerland and Italy embarked on a unique diplomatic journey, characterized by pragmatism and cooperation rather than contention. Recognizing that the physical basis of their 1941 treaty had been altered by climate change, the two neighbors initiated a joint survey in 2018. Expert teams from both national surveying agencies worked collaboratively, using high-precision GPS and aerial photography to map the new reality of the terrain. The goal was not to contest territory but to jointly define a new, stable, and legally sound frontier based on the current watershed line—the principle enshrined in the original agreements.

The process resulted in a minor territorial shift of approximately one square kilometer near the Theodul Glacier area, with the border moving slightly to follow the redefined rocky watershed. This adjustment was formalized through a treaty, signed in 2023, which both parliaments ratified without political conflict. The collaboration extended beyond mere cartography; it included joint monitoring of geological stability and environmental changes in the affected zone. This peaceful adaptation stands as a notable example of international law functioning as intended, allowing for orderly change in response to unforeseen circumstances. It underscores a shared understanding that the adversary is not each other, but the broader environmental shifts affecting the entire region. For alpinists planning a climbing the Matterhorn expedition, the change is largely cartographic, though it underscores the rapidly changing nature of the mountain itself.

Environmental Challenges and the Future of Alpine Conservation

The re-drawn border near the Matterhorn is but a local symptom of a vast, regional crisis. Across the Alps, glaciers are in wholesale retreat, losing volume at an accelerating pace. This loss is not merely an aesthetic or symbolic concern; it destabilizes the very fabric of the mountains. Glaciers act as a glue, cementing rock faces and supporting high-altitude slopes. Their disappearance leads to increased geological hazards, which now present critical challenges for conservation and human activity:

- Increased Rockfalls and Landslides: thawing permafrost, the permanently frozen ground that binds rock together, is becoming widespread. This leads to more frequent and larger rockfalls, endangering climbing routes, hiking trails, and mountain infrastructure like cable car stations and huts.

- Hydrological Disruption: glaciers are vital natural reservoirs, releasing meltwater steadily through the summer. Their decline threatens water supplies for agriculture, hydroelectric power, and communities in the valleys below, exacerbating droughts.

- Impact on Tourism and Local Economies: ski resorts at lower altitudes face increasingly unreliable snow cover, while iconic glacial landscapes that attract visitors are vanishing. Mountain guides must constantly reassess route safety due to changing conditions.

- Ecosystem Shifts: as the cryosphere shrinks, Alpine flora and fauna are forced to migrate upwards, competing for diminishing habitats and potentially facing local extinction.

Addressing these interconnected issues requires a multi-faceted approach that transcends national borders as effectively as the border cooperation between Switzerland and Italy. Conservation efforts are expanding to focus on ecosystem resilience, disaster risk reduction, and sustainable tourism models that are less dependent on fragile ice and snow. The urgency for concerted climate action is palpable, as further warming could see the disappearance of most Alpine glaciers by the end of this century. The story of the moving border is ultimately a powerful, tangible indicator that climate change is already rewriting the physical and political map, demanding adaptation, collaboration, and a renewed commitment to protecting the vulnerable Alpine environment for future generations.