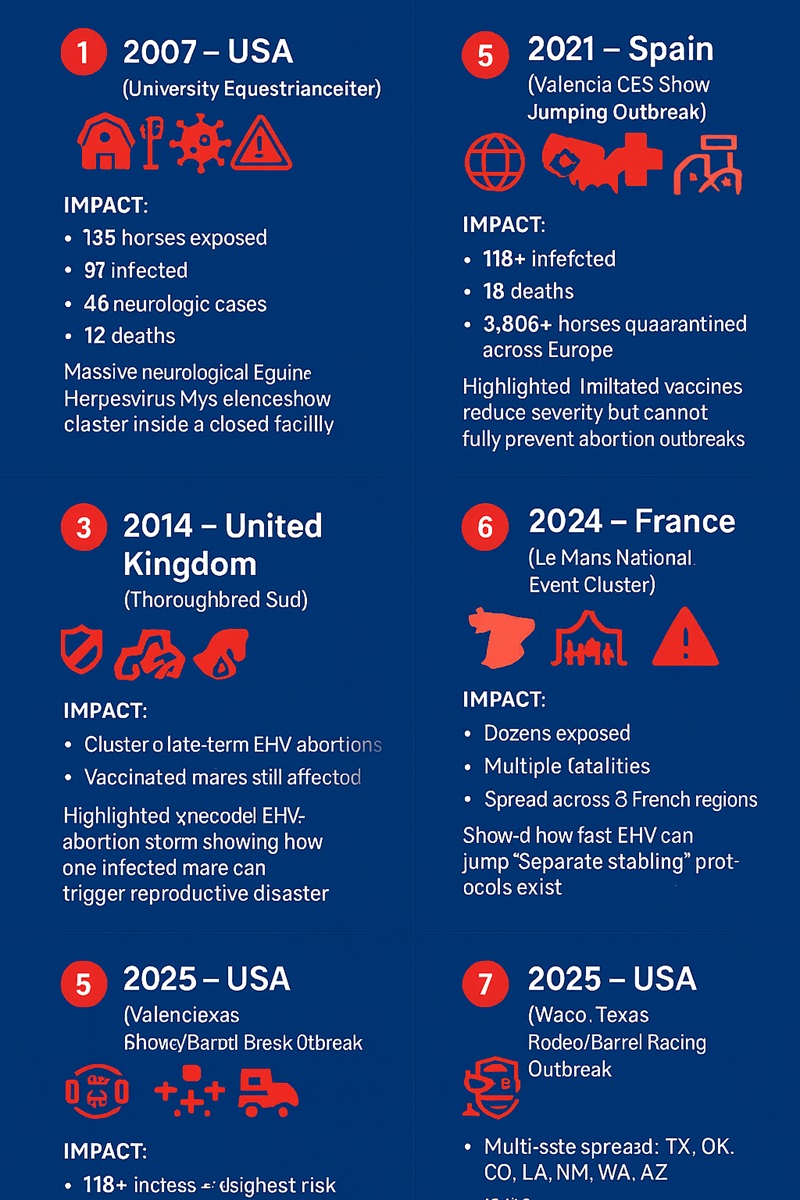

The 2025 horse virus outbreak has grown much faster than anyone expected. It began with a group of sick horses after the WPRA World Finals & Elite Barrel Race in Waco, Texas. What looked like a small cluster has now become a multi-state equine health crisis. Cases of EHV-1 and the neurologic form, EHM, have been confirmed across the country.

Horses that competed in Waco—or even passed through the venue—traveled home soon after. Many carried the virus with them. This has led to new cases in Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Washington, and South Dakota.

For trainers, owners, breeders, and event organizers, the speed of the outbreak has been alarming. Within days of the event, horses developed fevers, showed neurologic signs, and tested positive for EHV-1. The virus has already caused major event cancellations, including a key San Antonio Stock Show & Rodeo qualifier. Several arenas and rodeo facilities in Texas have also shut down temporarily to stop further spread.

This outbreak is serious. EHV-1 spreads fast, survives on surfaces, and can move quietly between barns through travel, shared gear, and even human contact. The neurologic form, EHM, can appear suddenly, which makes the situation especially worrying for owners.

What Is EHV—and Why Is This Virus So Serious?

Equine Herpesvirus (EHV) is an umbrella term for several virus strains that affect horses, with EHV-1 and EHV-4 posing the biggest threats during outbreaks. Both viruses spread quickly and cause respiratory disease, but EHV-1 carries additional risks—including neurological complications known as equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy (EHM).

Why veterinarians worry about EHV-1

- It spreads easily in barns and trailers

- It can cause abortions in pregnant mares

- It can trigger sudden neurologic decline

- It leads to significant facility shutdowns and quarantines

The neurologic form, EHM, is rare but devastating, causing hind-end weakness, difficulty standing, and in some cases, the inability to rise.

EHV is common, but outbreaks happen when the virus takes advantage of close quarters, high-stress environments, and interstate movement.

Where the Horse Virus Outbreak Has Spread in the U.S.

The current horse virus outbreak isn’t hypothetical—it’s a live, evolving situation that started with a single high-profile event and spread across much of the country in just a few weeks.

How the 2025 EHV-1 Outbreak Started

In early November 2025, horses gathered in Waco, Texas, for the Women’s Professional Rodeo Association (WPRA) World Finals and Elite Barrel Race, held November 5–9. In the days that followed, veterinarians began seeing horses with fever and neurologic signs that tested positive for Equine Herpesvirus-1 (EHV-1), specifically the neurologic form known as equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy (EHM).

What looked like a local issue at first quickly revealed a much wider footprint as exposed horses returned home across state lines and additional cases surfaced.

Where Cases Are Being Reported Now

According to updates from the Equine Disease Communication Center (EDCC) and multiple state agencies, this outbreak is now clearly multi-state:

- The index cluster has been traced back to the Waco, Texas, barrel racing and rodeo events.

- As of November 25, 2025, at least 33 confirmed EHV cases linked to the Waco event have been reported in eight states: Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Colorado, New Mexico, Washington, Arizona, and South Dakota.

- Earlier updates noted confirmed neurologic EHM cases and additional EHV-1 positives in Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado, and Louisiana, with at least two horses euthanized in Texas due to severe disease

Several other states, including Missouri, North Dakota, and New Mexico, have issued alerts or confirmed individual cases connected to horses that traveled to or from these Texas and Oklahoma events, underscoring how quickly EHV follows the competition circuit.

How It Was First Picked Up

The outbreak was first recognized when horses returning from the Waco events began showing:

- High fevers

- Neurologic signs such as hind-limb weakness and incoordination

- Positive EHV-1/EHM test results

Reports from veterinarians and event organizers triggered rapid notifications to state animal health commissions, the EDCC, and national equine industry groups.

From there, the pattern became clear: horses that had never shared a barn but did share the same competition schedule were turning up sick in multiple states.

Real-World Impact: Closures, Cancellations, and Travel Disruptions

The ripple effects on the horse industry have been immediate:

- The San Antonio Stock Show & Rodeo canceled a key qualifier event in Uvalde, Texas, scheduled for November 19–22, after the outbreak was linked to the Waco barrel racing finals.

- Multiple arenas and rodeo facilities in Texas—including venues around Houston, La Porte, Santa Fe, Magnolia, Willis, Winnie, and Galveston’s Jack Brooks Park—have temporarily closed or restricted events to limit spread.

- Some rodeo associations have canceled or scaled back upcoming events, and others are shifting to stricter entry, temp-check, and isolation policies for competing horses.

For owners and trainers, this translates to sudden changes in show calendars, travel plans, and barn management protocols, even if their horses aren’t yet in a known hot zone.

Key Numbers at a Glance (As of November 25, 2025)

You can summarize these data points in a callout box or sidebar:

- Index event: WPRA World Finals & Elite Barrel Race, Waco, Texas (Nov 5–9)

- Confirmed linked cases: 33+ horses with EHV (including EHM) associated with that event

- States with confirmed linked cases so far:

TX, OK, LA, CO, NM, WA, AZ, SD - Reported euthanasias: At least two horses in Texas due to severe EHV-1/EHM

Trend: Case numbers expected to rise further as exposed horses are tested and monitored over the coming 1–2 weeks.

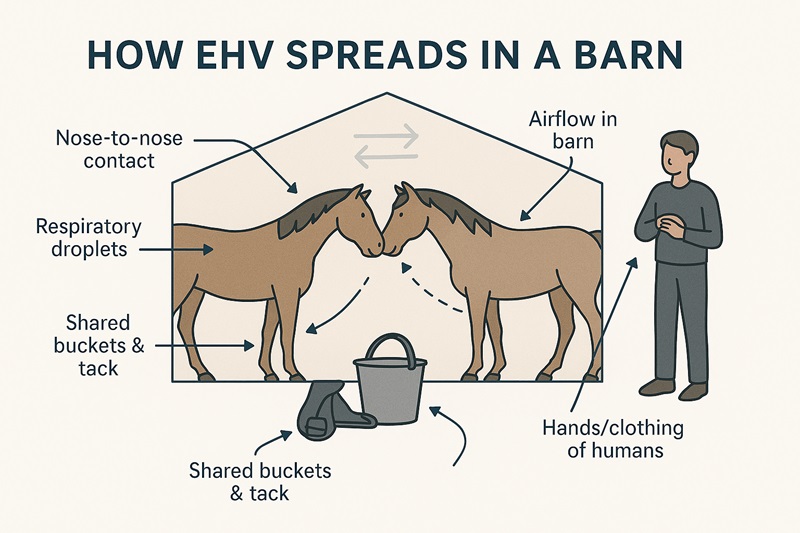

How EHV Spreads: The Science Behind Fast Transmission

EHV is not airborne in the way measles or COVID-like viruses are. Instead, it spreads through a mix of close respiratory contact, contaminated surfaces, and human involvement. Here’s how:

- Nose-to-Nose Contact

Horses greeting each other over stall doors, fences, and at the wash rack can pass the virus within seconds.

- Respiratory Droplets in Enclosed Barns

Coughing, snorting, or simply breathing in poorly ventilated aisles can move viral particles through the air.

- Contaminated Surfaces

Items that travel between horses—lead ropes, buckets, bits, grooming tools—can harbor the virus.

- Human Spread

Grooms, farriers, trainers, and owners can unintentionally transport the virus on clothing, hands, and equipment.

- Stress, Travel & Immune Suppression

Hauling, hard competition schedules, and winter confinement all lower immunity, making horses more susceptible after exposure.

How EHV Impacts Horses, Other Animals, and the Barn Environment

The recent multi-state outbreak has shown a hard truth: EHV does not cause only short-term illness. When it spreads through barns, racetracks, and breeding farms, the damage can be deep and long-lasting. It affects a horse’s body, the barn environment, and even the larger equine community.

Below is a simple look at how EHV harms the horse from the inside—and how it affects the spaces and animals around it.

How EHV Damages a Horse’s Body: More Than a Respiratory Virus

At first, EHV may look like a mild cold. A horse may show a fever, nasal discharge, or seem a bit tired. But inside the body, the virus is doing much more.

A. The Respiratory System: Breathing Problems and Performance Loss

EHV starts in the upper airway. It causes swelling and irritation that make it harder for the horse to breathe. Airflow narrows, and oxygen levels drop.

For performance horses, this can feel like trying to run a race with a bad cold. They simply cannot get enough air, so their stamina and speed fall fast.

Common outcomes include:

- Reduced stamina

- Prolonged recovery times after exercise

- Temporary performance declines that linger well beyond the initial infection

Even after clinical symptoms fade, many horses require weeks or months to regain full respiratory strength.

B. The Nervous System: When EHV Becomes Neurologic EHM

The most feared complication of EHV-1 is equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy (EHM)—a neurologic storm caused by inflammation and damage to blood vessels feeding the brain and spinal cord.

Signs often appear suddenly:

- Unsteady or wobbly gait

- Weakness in the hind limbs

- Difficulty rising

- Loss of bladder control

For some horses, these symptoms progress rapidly. A horse that is shaky in the morning may be unable to stand by evening. This is why EHM cases require immediate veterinary care, strict isolation, and, in severe cases, euthanasia for humane reasons.

This is not a common outcome—but it is the one that keeps veterinarians, trainers, and barn managers awake at night.

C. Reproductive Damage: The Silent Threat to Breeding Farms

For pregnant mares, EHV brings a different set of dangers.

The virus can cross the placental barrier, leading to:

- Abrupt abortion (often without warning)

- Premature or weak foals

- Potential outbreaks within the broodmare band

A single EHV abortion often triggers a full-farm lockdown, meaning halted breeding operations, isolation zones, and strict biosecurity for weeks.

For farms operating on seasonal timelines, these losses are not just emotional—they can reshape an entire year’s breeding program.

Long-Term Impacts on Horses: Recovery Isn’t Always Linear

EHV is a herpesvirus, which means once a horse is infected, the virus can lie dormant for life. Stress, travel, and illness can reactivate it—similar to cold sores in humans.

Some horses experience:

- Persistent weakness or coordination issues after EHM

- Long-term respiratory sensitivity

- Reduced athletic performance

- Higher vulnerability to future infections

While many horses recover well, others never return to their previous form, especially in high-intensity disciplines like barrel racing, eventing, or racing.

Does EHV Affect Other Animals? Here’s the Clarifying Science

EHV is species-specific.

Humans cannot get sick from it. Dogs, cats, cattle, and wildlife are not biologically susceptible.

However—there’s an important catch:

Humans can carry the virus between horses.

Not in their bloodstream, but on:

- Hands

- Clothing

- Jackets

- Boots

- Grooming tools they touch

This “mechanical transmission” is a major driver of multi-state outbreaks. A person leaving one infected barn can unknowingly bring the virus to the next.

Donkeys, mules, ponies, and zebras can get EHV, but horses remain the primary risk group.

Environmental Impact: How EHV Survives in the Barn Ecosystem

Outdoors, sunlight and airflow help break down viral particles.

Indoors, the story changes dramatically.

EHV can persist on:

- Stall walls and latches

- Water buckets

- Halters and lead ropes

- Brooms, rakes, pitchforks

- Shared tack and grooming kits

- Trailer dividers and tie rings

The virus survives longer in:

- Cold, moist environments

- Poorly ventilated barns

- High-traffic stalls and shared spaces

This is why winter show seasons and high-density stabling environments are often associated with larger outbreaks.

Disinfecting with proven virucidal agents—like accelerated hydrogen peroxide or freshly mixed bleach—is essential, but contact time matters. A quick wipe is not enough.

Economic, Welfare, and Industry-Wide Impact

A. Financial disruption

An EHV outbreak doesn’t just threaten horse health—it disrupts entire business models.

Owners face:

- Vet bills

- Emergency testing

- Quarantine expenses

- Lost training weeks

- Event cancellations

- Insurance implications

- Decreased sale values for recently exposed horses

A single virus event can cost the industry hundreds of thousands of dollars.

B. Welfare and emotional impact

EHM cases are emotionally draining.

Owners watch their horses lose balance, struggle to stand, or fight through neurologic decline. Euthanasia decisions can come suddenly and without warning.

C. Community impact

- Rodeos cancel qualifiers

- Shows shut down

- Hauling routes change

- Breeding farms enter lockdowns

- Trainers pause operations

- Transport companies modify schedules

An EHV outbreak alters the rhythm of the entire equine community—from small backyard barns to national rodeo circuits.

EHV is not a simple seasonal virus. It affects the horse’s lungs, nervous system, and reproductive health. It can also harm long-term performance. The impact does not stop with the horse. It spreads into barns, breeding programs, travel plans, equine businesses, and even whole regional economies.

Knowing how EHV works—from the smallest cell to the entire stable—is the first step in protecting horses during the 2025 outbreak.

Early Symptoms of EHV You Need to Watch For

During an outbreak, fever is often the first red flag. Many barns catch EHV early simply by taking temperatures twice a day.

Common early signs

- Fever above 101.5°F

- Nasal discharge

- Lethargy or unusual quietness

- Coughing or reduced appetite

Neurologic (EHM) symptoms

- Hind-limb weakness

- Stumbling or wobbly gait

- Difficulty urinating

- Inability to stand

These neurologic cases require immediate veterinary intervention.

What You Should Do Today If You’re in an Affected Region

When EHV cases appear in your area—or anywhere along your horse’s travel route—swift action is your best defense.

- Stop All Horse Movement

No clinics, no shows, no hauling. Virus spread almost always accelerates through travel.

- Begin Temperature Checks

Record temperatures twice daily. A rising temp is often the first—and only—early warning.

- Establish Quarantine Protocols

Any horse with fever or exposure should be isolated for 21–28 days with:

- Separate handler

- Separate equipment

- No shared airflow if possible

- Contact Your Veterinarian

PCR testing is the gold standard for confirming infection.

- Alert Your Boarding Barn or Event Organizer

Outbreak control is community-based. Transparency saves horses.

Barn Biosecurity: Your Most Powerful Prevention Tool

During an outbreak, every barn should operate like a small biosecure facility. Effective biosecurity isn’t complicated—it’s consistent.

Daily hygiene practices

- Assign personal buckets, grooming kits, and tack

- Disinfect stall doors, cross-ties, and aisleway hardware

- Use gloves or hand sanitizer between horses

- Limit visitors and nonessential handlers

Improve ventilation

Open barn doors, add fans (without blowing directly between stalls), and reduce dust buildup.

Reduce stress

Well-rested, well-hydrated, and well-fed horses have stronger immunity.

Should You Travel to Shows or Trail Rides Right Now?

During a multi-state EHV outbreak, travel is the single largest risk factor.

You should reconsider travel if:

- Your state or region has confirmed cases

- You board at a high-traffic barn

- You plan to attend large indoor winter shows

If you must travel

- Sanitize trailers before and after use

- Avoid shared water sources at events

- Request on-site temperature monitoring

- Keep horses from touching others over stall walls

Event organizers should provide isolation stalls, pre-arrival health forms, and strict temperature checks for all attendees.

Treatment & Recovery: What Owners Should Expect

There is no cure for EHV, but supportive care improves outcomes dramatically.

Typical treatment includes:

- Anti-inflammatory medications

- Fluids for hydration

- Antiviral medications in some cases

- Bladder support for neurologic horses

Most respiratory cases recover fully with rest. Neurologic cases require intensive care, sling support in some situations, and close monitoring.

Recovery timelines vary:

- Respiratory cases: 2–4 weeks

- Neurologic cases: Weeks to months

Can Vaccines Prevent an Outbreak? Yes—and No.

EHV vaccines are an important tool, but their role is often misunderstood.

What vaccines can do:

- Reduce severity of respiratory symptoms

- Reduce viral shedding

- Decrease risk in pregnant mares

What vaccines cannot guarantee:

- Full prevention of neurologic EHM

- A virus-proof barn

- Immunity during high-stress travel

Still, a well-timed vaccination schedule reduces overall outbreak severity, especially in show barns and breeding facilities.

Environmental Hygiene: The Overlooked Factor

Disinfection is critical—EHV can linger on surfaces for hours to days depending on temperature and humidity.

Use virucidal disinfectants with proper contact time:

- Accelerated hydrogen peroxide

- Quaternary ammonium compounds

- Bleach solutions (freshly mixed)

Clean high-touch surfaces often:

- Stall latches

- Lead ropes

- Aisleway light switches

- Grooming tools

Manure management and proper waste disposal further reduce viral load in the environment.

When Will This Outbreak Slow Down?

Outbreaks tend to fade when:

- Movement stops

- Cases are isolated early

- Barns adopt strict biosecurity

- Events enforce regulations

However, new clusters can appear when:

- Travel resumes too quickly

- Infected but asymptomatic horses move between barns

- Facilities fail to disinfect equipment or shared spaces

Seasonality also plays a role—winter barns with low ventilation are especially vulnerable.

FAQs

Is this horse virus outbreak deadly?

The neurologic form (EHM) can be fatal. Respiratory cases are usually manageable with care.

Can vaccinated horses still get EHV?

Yes, but they often have milder symptoms and shed less virus.

Can humans spread EHV between barns?

Humans can’t get EHV, but they can carry it on hands, clothing, and equipment.

How long does EHV survive on surfaces?

From several hours to a few days, depending on conditions.

Can horses travel during an outbreak?

Only when absolutely necessary—and only with strict veterinary guidance.

Conclusion: Fast Action Saves Horses

A horse virus outbreak doesn’t need to become a barn-wide crisis. With quick temperature checks, strict quarantine, smart travel decisions, and everyday biosecurity, you can protect your horses and prevent further statewide spread.

In moments like this, calm vigilance is more powerful than panic. The steps you take today can keep your horses safe—and help your entire equestrian community ride out this outbreak together.