When global leaders, scientists, activists, and Indigenous communities gathered in Belém for COP30, expectations were monumental. Not simply because the Amazon symbolized both the wonder and fragility of our planet, but because the summit arrived at a tipping point: the world needed more than pledges—it needed execution, enforcement, and equity.

What followed was a summit with big wins and clear gaps. Some areas finally moved forward, such as adaptation funding, Indigenous leadership, and new roadmaps for key sectors. But one major goal remained out of reach: a firm global plan to phase out fossil fuels.

For people in higher education, these outcomes matter in two ways. They shape the work of climate researchers, and they guide how we teach the next generation of climate leaders.

A COP of Mixed Victories

“Progress Where It Was Long Overdue”

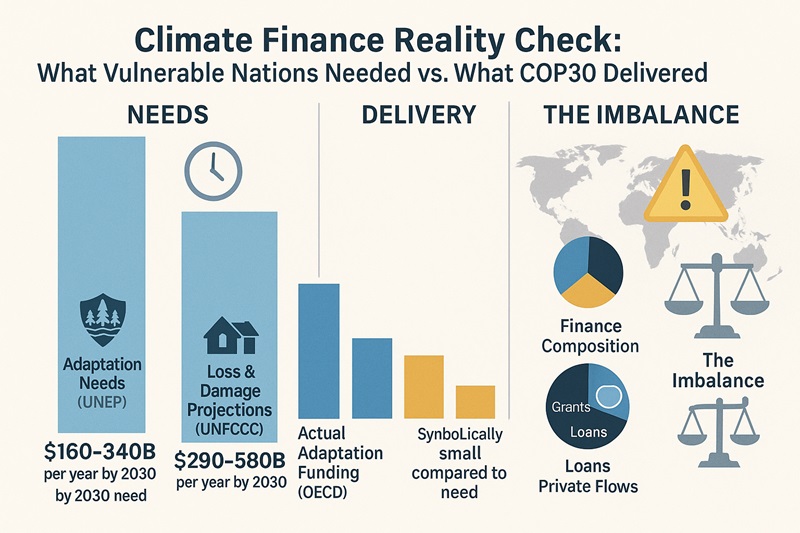

Belém delivered measurable movement on adaptation finance and forest protection. The OECD reported that while developed nations met the $100 billion annual climate finance target only by 2022—two years late—adaptation remained underfunded, comprising just 25-28% of total flows. COP30, building on this deficit, prioritized expanding adaptation channels.

A notable shift was the alignment with UNEP’s Adaptation Gap Report, which estimates developing countries need $160–340 billion annually by 2030. COP30 discussions acknowledged this gap and called for scaling grant-based financing over loans, reducing conditionalities, and enhancing direct-access channels for vulnerable nations.

The Amazonian context helped center forest protection and Indigenous sovereignty. Unlike earlier COPs where Indigenous voices were symbolic or sidelined, Belém structured participation mechanisms that made them co-authors of decisions. Their message: forest protection is less about technology and more about governance, justice, and land tenure security.

“From Pledges to Practical Frameworks”

Perhaps most promising was the maturation of the COP “action agenda.” COP30 unveiled sectoral accelerators—concrete decarbonization roadmaps for energy, agriculture, steel, cement, and transport. These were not abstract intentions but policy frameworks with indicators, financial pathways, and public-private implementation coalitions.

This reflected a departure from the voluntary pledges of COP26 and COP27, edging toward verifiable, metrics-driven planning. For climate professionals and students alike, this represents a curriculum shift from theory to systems thinking and real-world solutions.

Where COP30 Fell Short

“The Fossil Fuel Elephant Remained in the Room”

Despite mounting scientific urgency, COP30 failed to deliver a unified, time-bound global agreement on phasing out fossil fuels. The IPCC has reiterated that global emissions must peak before 2025 and decline rapidly to keep warming below 1.5°C. Yet the final text, negotiated under fierce resistance from OPEC+ members and fossil-fuel-reliant economies, avoided firm commitments.

While some blocs, including the EU and AOSIS (Alliance of Small Island States), pushed for a phasedown with defined milestones, opposition from petro-states diluted the language to “accelerating clean energy transitions.”

This ambiguity sustains a gap between science and politics. Youth movements, climate-vulnerable nations, and civil society criticized the outcome as a delay tactic that undercuts the Paris Agreement’s core promise.

“Finance: Expanded, Yet Inadequate”

Adaptation finance increased, but not to scale. The imbalance persisted: – Too many loans, not enough grants. – Funding mechanisms favored multilateral banks, not direct access. – Conditions remained complex, slow, and donor-controlled.

The Loss and Damage Fund—formally established at COP27—saw technical progress. Governance structures were refined, but pledges remained modest. Total contributions were far from meeting the scale of damages, which are estimated at $290–580 billion annually by 2030 (UNFCCC 2022).

For many developing nations, especially LDCs and African Group of Negotiators, the takeaway was familiar: words outpaced money.

“Article 6 Still a Work in Progress”

Carbon market rules under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement remained incomplete. COP30 made headway on transparency and integrity standards, but key issues—including double counting, human rights safeguards, and governance of crediting mechanisms—were unresolved.

This creates uncertainty for voluntary and compliance markets. For universities and climate finance researchers, the gap underscores the need for stronger monitoring frameworks, equity assessments, and open-data infrastructures.

“The Ambition Gap Persists”

UNEP’s 2023 Emissions Gap Report showed that current NDCs put the world on a 2.5–2.9°C pathway. COP30 did not significantly change this trajectory. While stocktake alignment improved, few countries upgraded their 2030 targets. Political cycles, economic headwinds, and geopolitical tensions (e.g., energy security in Europe and Asia) dominated negotiators’ risk calculus.

UK’s Role: Leadership by Rhetoric, Not Reinforcement

The UK arrived with the legacy of COP26 in Glasgow and strong research credentials. Speeches championed net-zero innovation, clean-tech investment, and global climate leadership.

Yet: – No significant increase in climate finance. – No new emissions reductions beyond existing targets. – No diplomatic push on the fossil fuel phase-out.

The contrast between past leadership and present hesitance was noted by both domestic and international observers.

For UK universities, this has implications. Our global influence in climate science and policy is substantial—but without national alignment, research impact risks becoming isolated from diplomatic clout.

What COP30 Means for Higher Education

Universities were not passive observers at COP30. Academic delegations contributed to adaptation research, Article 6 transparency discussions, and Indigenous knowledge integration. The outcomes signal both a validation and a challenge to higher education institutions worldwide.

1. Shift Research from Diagnosis to Design

The age of climate denial has passed. The era of solution design is here. Universities must reorient research priorities toward applied science: – Scaling community-based adaptation in low-income countries. – Building financial mechanisms for just transitions. – Innovating climate-resilient infrastructure. – Operationalizing nature-based solutions at landscape scale.

Institutions must invest in transdisciplinary centers that engage with governments, Indigenous coalitions, multilateral agencies, and private financiers.

2. Mainstream Climate Across Curricula

Climate literacy cannot remain confined to environmental studies. COP30 reinforces the need for climate integration across disciplines: – Business: Climate risk, finance, ESG reporting. – Engineering: Decarbonized design, life-cycle analysis. – Education: Climate pedagogy, curriculum reform. – Law and Policy: Climate justice, loss & damage, compliance. – Health Sciences: Climate epidemiology, disaster response.

Leading institutions have begun climate-MBA tracks, climate-data minors, and joint sustainability-law degrees. These models must scale globally.

3. Walk the Talk: Universities as Living Labs

Students increasingly judge institutions by action, not statements. Campuses must model: – Carbon neutrality with open data dashboards. – Procurement aligned with net-zero targets. – Divestment from fossil-intensive portfolios. – Nature-positive biodiversity policies.

This credibility is essential to attracting the next generation of climate-conscious students, faculty, and funders.

4. Elevate Public Scholarship and Policy Impact

COP30 showed that trust and implementation are key. Academics must: – Translate research into policy briefs and legislative testimony. – Collaborate with cities, communities, and corporations. – Communicate in accessible formats: op-eds, podcasts, toolkits.

The climate movement is as much a communications challenge as a technical one.

5. Recognize Students as Strategic Actors

Students are not just learners but co-creators of climate action. At COP30, youth leaders shaped narratives, demanded accountability, and launched social innovation platforms.

Universities must create: – Funding for student-led climate research and entrepreneurship. – Platforms for youth input into governance. – Fellowships for climate diplomacy and implementation.

The Path Ahead

COP30 will not be remembered as the summit that closed the emissions gap or revolutionized climate finance. But it may be remembered as the moment the center of gravity shifted: – From rhetoric to implementation. – From pledges to sectoral plans. – From donor-led finance to equitable access. – From extractive policy to Indigenous co-governance.

For higher education institutions, the message is clear: we are no longer just chroniclers of climate change. We are builders of its solutions.

We cannot wait for policy systems to catch up. We must: – Teach as if the crisis is present. – Research as if time is limited. – Lead by example. – Partner across boundaries.

The generation that inherits the consequences of COP30 is already in our classrooms. Our task is not just to prepare them to adapt—but to lead.

Meta: An in-depth look at COP30’s progress and shortcomings—adaptation gaps, Loss & Damage finance, stalled fossil fuel negotiations, Article 6 challenges—and how these outcomes reshape climate research, education, and university leadership.